2025 Electronic Badge

Dec 29, 20252025 Badge

I started making badges for a Christmas party a few years ago, and each year I’ve upped the complexity and cost, as my confidence in my own skills and my mates’ construction skills grew.

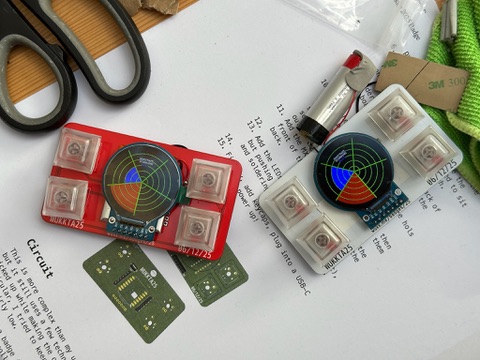

My first badge was a simple multivibrator powering some LEDs, the next was a charlieplexed LED matrix with an ATtiny, and for this one I pulled out all the stops and went truly crazy. This year I designed a device which could detect others, used MX switches for ultimate clickability and had a display!

I didn’t get all the features I originally wanted, but the result was pretty cool, battery powered, rechargeable, worked fairly well… and was a bit of a pain to build and program. Here’s the back story.

One click quick disclaimer: I used Amp to help with the programming, so if that stuff annoys you, skip the section marked 🤖🔫 (but don’t, it’s actually interesting)!

Parts

I got pretty obsessed designing this badge in late summer, and back in August I started looking at displays. I knew these would be the core of the device but I wanted to keep the cost relatively low, so I scoured AliExpress until I found some reasonably priced round TFT LCDs (GC9A01), for about £2. Plenty of Arduino projects used these, so they seemed like a good choice.

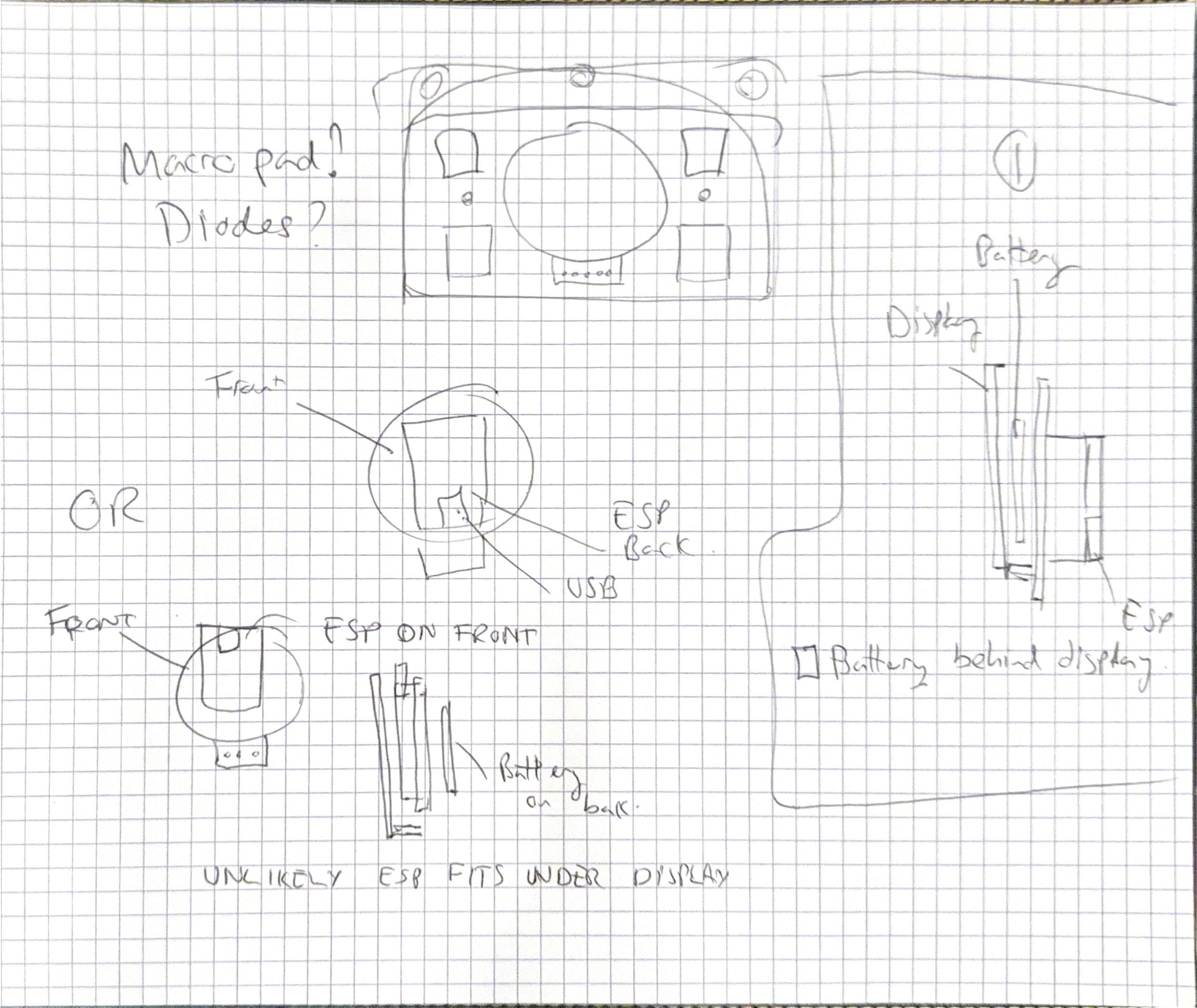

I ordered a bunch then started thinking about physical designs and looking through my boxes of parts and sketching ideas.

After a while I settled on something that looks a bit like a game controller, with switches towards the edges and knew I wanted to use cheap ESP32-C3 modules, so bought a few from amazon. As you’ll see later I didn’t end up using these, but they were a good start.

Original rough design sketch - such skill and beauty

When the displays arrived I was eventually able to get them working using the Arduino IDE and the bodmer TFT_eSPI library, provided I pinned an old version of the esp32 board library. In retrospect using eTFT_SPI was a mistake, and I should really have used something else, but I didn’t know this at the time.

It’s really not easy for a relative beginner to pick the best Arduino libraries, and a lot of the time the best information on what’s available is buried in forums, reddit and GitHub issues.

The TFT_eSPI library requires a special header file outside of your project directory (which is bizarre but works) and having to pin the esp32 board package to 2.0.14 meant I didn’t get a load of cool new features (like some newer flash filesystems), but it didn’t stop me making progress. Not pinning to this version caused my ESP board to get stuck in a crash loop.

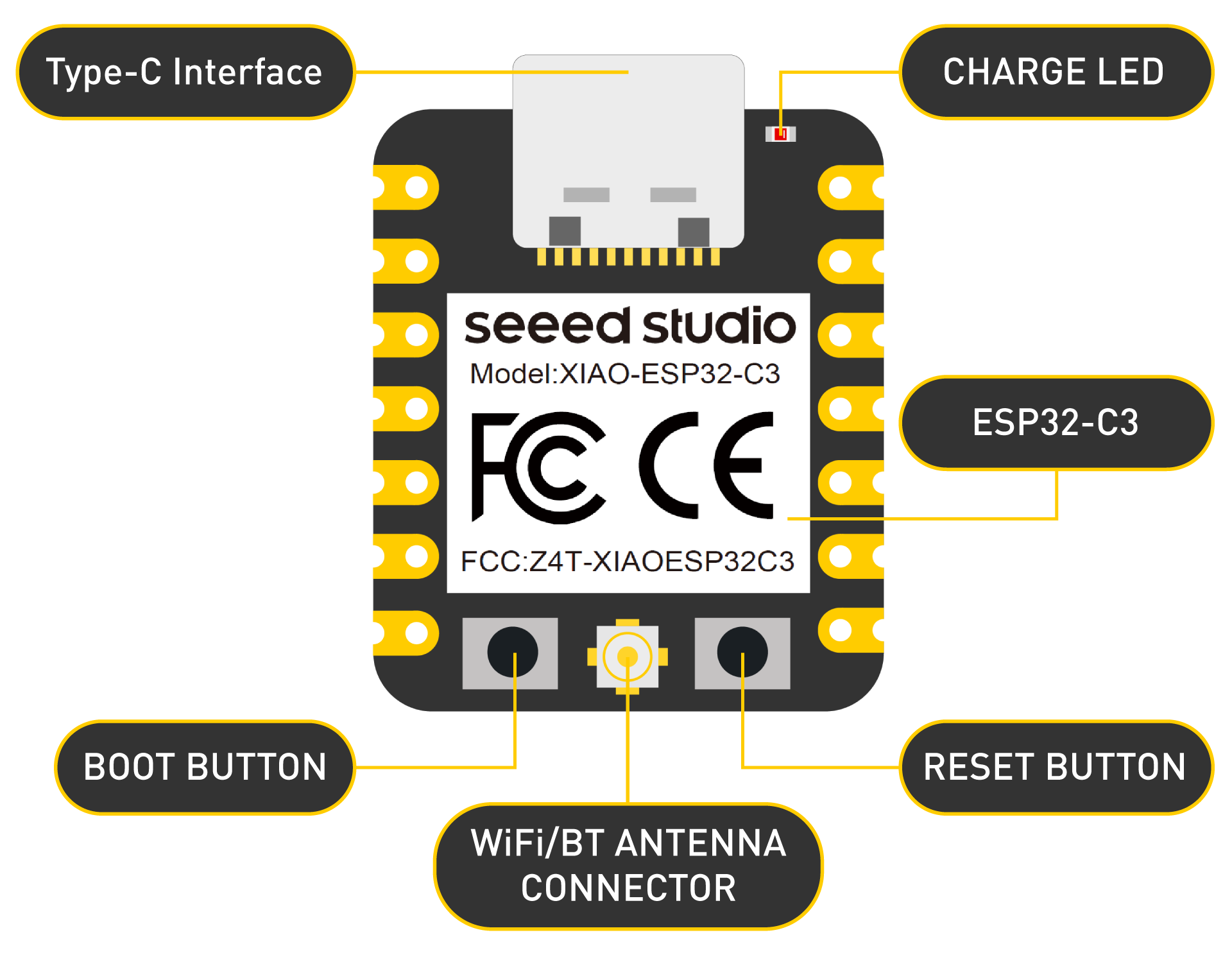

As you can see in my sketch, I knew I wanted a lithium battery sitting behind the display, so I ordered a bunch from AliExpress and started looking for battery charge controller chips. Everything I could find was pretty expensive, but eventually I realised that Seeed Studio’s XIAO ESP32-C3s have battery charging chips build-in, so I ordered a bunch of them to act as the brains of the badges. I paid about $28 for 6 by ordering direct during a sale (and later ordered more from the UK, for a bit more).

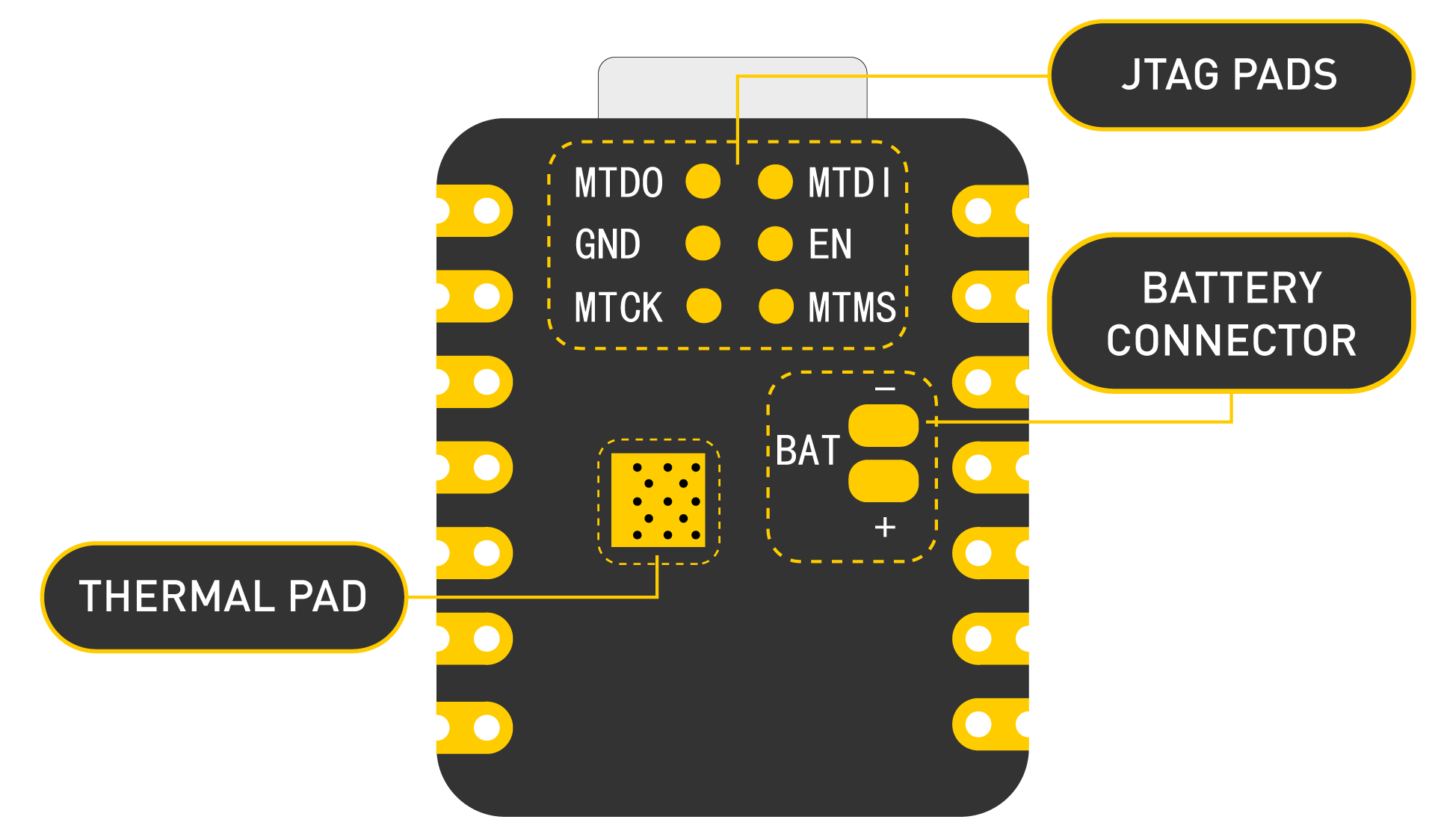

The XIAO devices have plenty of great docs and decent support, so they were a good choice. However, the battery pads are on the base of the device, meaning some SMD soldering would be needed!

Eventually, I gave up waiting for my AliExpress lithium batteries and bought a bunch from eBay. These cost about £5, which was frustrating, but at least they arrived.

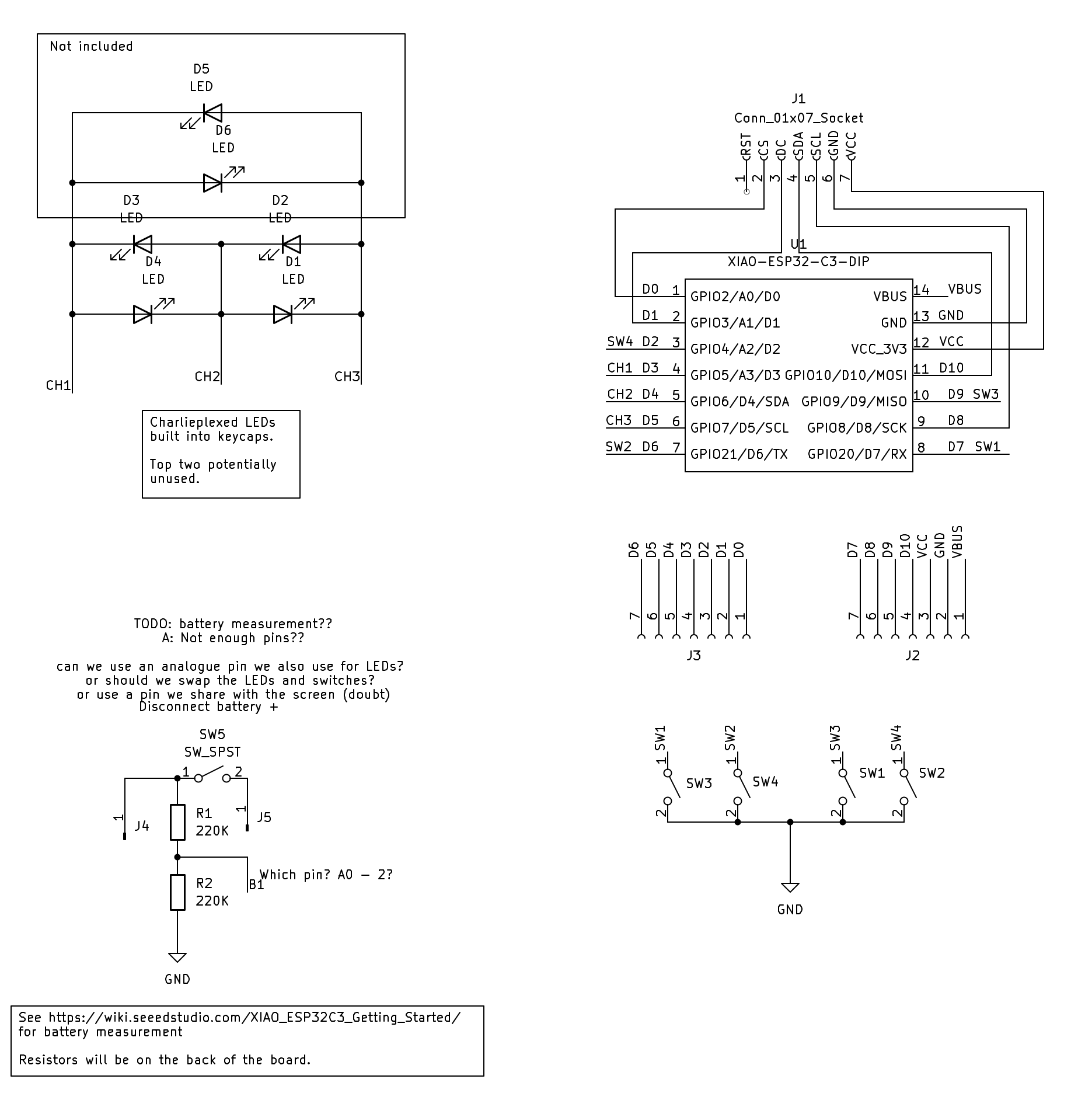

Finally, I found a bunch of MX switches left over from previous projects and realised I could use them pretty easily. I also decided to add LEDs because my switches had slots for LEDs, and I calculated that I’d have enough pins on the ESP32 if I charlieplexed the LEDs (as I did last year). This all worked pretty well in prototyping, so I moved to schematic capture and then PCB design.

Circuit capture

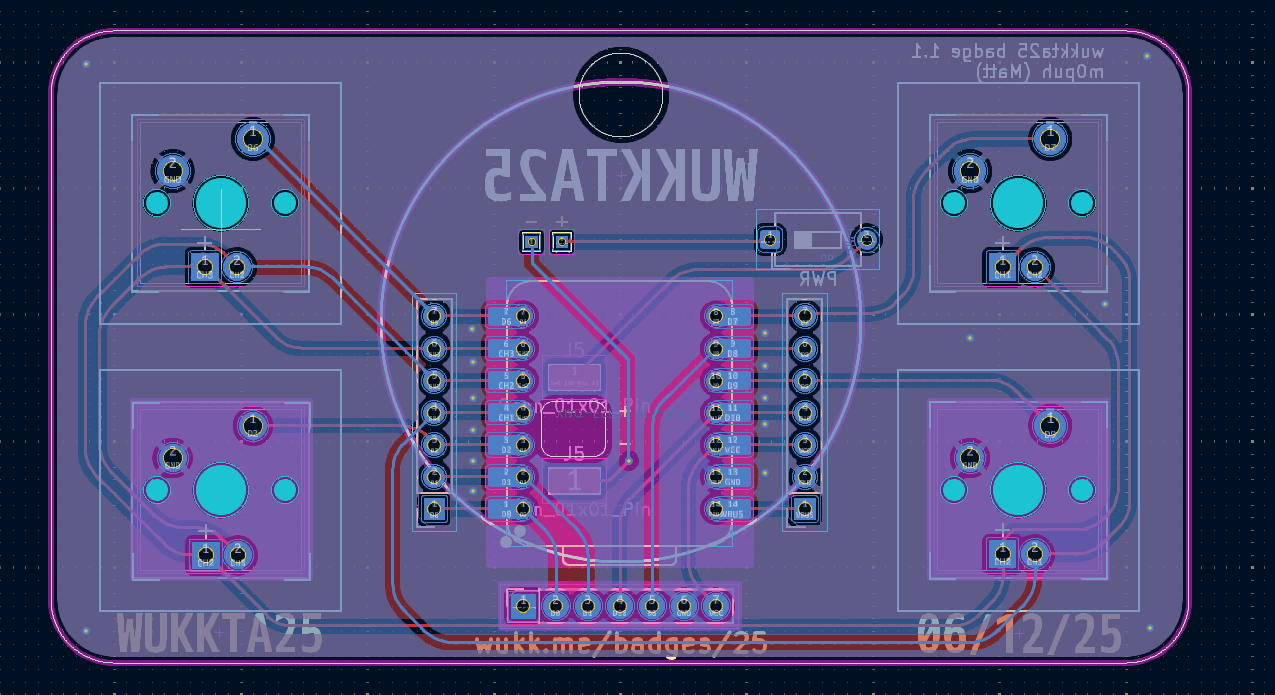

I drew up my circuit idea into KiCad, using plenty of labels to reduce the number of interconnecting wires. I also left myself a bunch of notes in the schematic, including some extra unused circuitry for measuring battery voltage (omitted out because if complexity) and a couple of extra LEDs I didn’t need.

I then assigned footprints (which attaches physical part designs to the components in the schematic), and during this stage I had to download some extra packages for the switches, LEDs and ESP32. If you’re new the KiCad I’d recommend watching some YouTube videos on how to do all this as the learning curve is steep.

Picking footprints is a massive pain, because you have to work out what you actually want to use, so this last section actually hides a lot of work, especially if you want to use parts that don’t cost an absolute fortune! The KiCad footprint library is already pretty large, and a huge number of parts on AliExpress have footprints identical to bits you’ll find on Mouser for 10x the price, but you’ll still end up doing a lot of research here, and grabbing extra downloads.

PCBs

Designing PCBs is always fun and frustrating, but I’m absolutely not an expert. I don’t let that stop me, and you shouldn’t either!

After importing the footprints from my schematic I set about adding the board edges and laying things out. As with the schematic capture this is hard work and if you’re new to it should should watch some tutorials.

I found lining everything up pretty painful, but it turned out really well. I remembered to enlarge a lot of the pads on the board to make soldering them easier, but I always forget a few things, and this was no exception. One silly thing I did was add long pads to allow directly soldering the ESP32 to the back of the board using the castellations, but then I forget to enlarge the pads on the top of the board, which is what my friends actually ended up soldering. I also used tiny pads for the battery connector, and I added rows of headers for debugging and later experimentation but forgot to connect one in the first run of boards, which was annoying as I had to add a bodge wire in my prototype, then order a new run of PCBs. Thankfully runs of 10 boards came to about £8 including slow shipping.

The physical design of the battery connections is something I really wasn’t happy with. I added a hole through the board to allow some surface mounted wires through, and then some pads to connect those to the front, but I put the associated labels on the back of the board (doh!). Construction of this part was hard work.

Ordering PCBs is pretty simple, KiCad has third-party packages which will automatically export a zip ready to upload to manufacturers, and I used JLCPCB for this. You can also find articles about the design rules each manufacturer requires you to follow (things like hole sizes, tolerances, silk screen resolution, etc.), and plug these into KiCad.

The final boards look great, and I got some in red and some in white.

Code

🤖🔫 trigger warning. AI use ahead, if you’re one of those people who can’t cope with reading about this, then skip ahead! I don’t have a hot take here, but I will tell you what I did.

The main features I wanted this badge to have were:

- scanning for other badges using Bluetooth Low Energy

- showing signal strengths in something reminiscent of a radar

- some sort of personalisation and images.

I also toyed with the idea of having proper BLE services, and maybe having the board work as a macropad, but ultimately I knew these things would be untouched after the day of our Christmas party so I didn’t go too far (who am I kidding, I spent bloody ages on this! I just didn’t go as far as I could have!).

As I said earlier, I spent a good while messing with the screen, pinning library dependencies and getting charlieplexing working. I also spent a lot of time on graphics, to get the radar style display working properly. I did all this by hand (and brain) and with those bits working, I started looking at Bluetooth Low Energy.

BLE is something I know very little about, and I started by messing with NimBLE examples but quickly got tripped up by trying to get the badge acting as both a client and server. I repeatedly saw crashes, regardless of what I tried, and it was at this point I dropped the intellectual challenge of trying to get this done purely by hand and fired up Amp’s CLI.

This helped enormously, as I was able to bounce ideas off the tool and have it do the bulk of the work. I would say that there was no point at which I didn’t understand my code, and that there were numerous cases where I had to fix generated code, but this saved me so much time and study and I’d go so far as saying that Amp literally made this project possible for me.

I did get into a little trouble with the code that’s triggered when interrupts fire (ISRs), because Amp kept wanting to add timers to them, which causes crashes, and it did sometimes use code that only worked with older versions of libraries. However, I was able to solve these issues with an AGENTS file (see AGENTS.md, by listing common corrections and documentation URLs. I only scratched the surface with Amp, but found it really powerful, largely accurate and very fast.

The end result was that I got what I wanted, by having it write most of the code and by removing the server code, and related functionality there. In an ideal world I’d have had the badges act as both clients and servers but even with Amp I wasn’t able to get that going with the time I had.

Later hacks

After the Christmas party I used Amp to reprogram the board to act as a Paw Patrol themed toy for my child. I downloaded some images, had Amp write a python script to convert them to C arrays and then update the badge functionality to scroll the images and flash the lights when various buttons were pressed. This went down really well and took about half an hour!

I also had it rewrite the code to make it a BLE macropad, and this was both super-fast and very effective, so worth a try. You can find the code for that on GitHub.

Later, I had Amp switch to a different LCD driver and build a simple UI with LVGL, for another project, and this did a great job (when I pasted the error messages from Arduino IDE to amp). I’m pretty sure that with some basic poking about it could automatically attempt compilation directly, but I’ve not looked at that yet.

Construction

Badge building is the point of the whole project, and I always try to write some decent instructions by thinking about the best order to build my projects, and this year I had the bright idea to put the URL to the instructions on the actual board. So you can find those at: https://wukk.me/badges/25/.

The actual construction was pretty straight-forward, but not that easy for the reasons I mentioned earlier.

Conclusions

This was another super-fun project that my friends and I enjoyed making and playing with.

I’ve been using the board for some other simple projects at home and I really like the design and layout. The battery sits neatly behind the screen and the buttons feel great to click on.

The end of my previous post on badges works just as well today as it did last year:

I’d encourage anyone interested in having a go to see what corners they can cut, resistors they can drop, pads they can expand, cheap components they can find and what they can mount on the back of the board to keep the sharp bits off clothes!

This design is also fun because you can hack on it and use it for other things, like a wireless macropad!

As before, you can find all the design files in GitHub. Total BOM cost was higher this time, but totally worth it for all these fun features and re-flashability.

| Component | Quantity | Cost (each) |

|---|---|---|

| LEDs (2x5x7 mm) | 4 | 2p |

| XIAO-ESP32-C3-DIP | 1 | £4 |

| MX Switches | 4 | 50p |

| SPST Switch | 1 | 10p |

| 7 Pin Socket (2.54mm pitch) | 2 | 10p |

| GC9A01 Display | 1 | £2 |

| 500 mAh lithium battery | 1 | £5 |